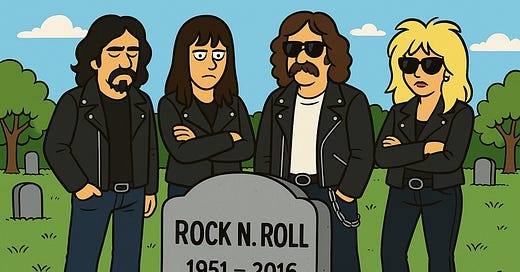

Rock and roll died on October 13, 2016, at the age of 65. The cause of death was respectability, a chronic condition that had been slowly suffocating our most cherished musical rebel for years before delivering the final, fatal blow.

Born on a sweltering day in Memphis in March of 1951, rock entered the world screaming through the amplified chaos of "Rocket '88," Ike Turner's overdriven guitar announcing the arrival of something that would spend the next six decades gleefully terrorizing parents, shocking preachers, and making teenagers do unspeakable things with their hips. From its very first breath, rock was magnificently, unapologetically, beautifully wrong.

Those early years were glorious in their complete disregard for propriety. Rock stumbled through the 1950s like a leather-jacketed delinquent, setting jukeboxes on fire and causing moral panic wherever it went. Elvis made grown women faint and grown men clutch their pearls. Little Richard shrieked like a beautiful banshee. Chuck Berry invented the mythology of teenage America while doing his duck walk across stages that segregation said he shouldn't even be allowed on.

Rock didn't just play music; it played with fire. It took the sexual tension that polite society spent so much energy suppressing and amplified it through Marshall stacks until the neighbors called the police. It grabbed the racial boundaries that America had so carefully constructed and smashed them together in three-chord harmony. It was dangerous because it was honest, and honesty has always been the enemy of respectability.

The 1960s should have killed rock with success, but instead, our beautiful rebel grew stronger, more defiant, more gloriously unhinged. Bob Dylan plugged in his guitar and committed folk music's most beautiful betrayal. The Beatles proved that mop-topped British boys could be more subversive than leather-clad Americans. Hendrix took the "Star-Spangled Banner" and tortured it into a question mark, making patriotism sound like feedback.

Rock survived Woodstock, though it emerged muddy and a little confused about whether it was a music genre or a political movement. It survived the 1970s by fragmenting into a dozen beautiful mutations: punk's three-chord manifestos, disco's hedonistic escapism, heavy metal's operatic darkness. Each offspring carried the original DNA: a fundamental suspicion of authority and an almost pathological need to be authentically, uncompromisingly itself.

The warning signs appeared in the 1980s. MTV wanted rock to be photogenic. Corporate sponsorship wanted it to be marketable. The Reagan era wanted it to be patriotic. Rock, being rock, responded by getting weirder, louder, and more theatrical, as if volume could drown out the creeping respectability. For a while, it worked. Hair metal was deliriously stupid but gloriously uncommercial in its commitment to excess. Alternative rock emerged from garages and college radio stations, maintaining the essential rock spirit: if the mainstream likes it, it's probably compromised.

But respectability is patient. It doesn't assault its victims; it seduces them. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame opened in 1986, and suddenly our beautiful rebel was being asked to wear a tuxedo to its own museum exhibition. Classic rock radio created a canon of acceptable rebellion, playing the same revolutionary songs so often they became elevator music. Rock stars started accepting knighthoods and cultural honors, their middle fingers slowly morphing into gracious waves.

The 1990s brought grunge, rock's last authentic gasp of generational rage. Kurt Cobain seemed to understand intuitively that success was poison, that the moment rock became comfortable with itself, it would cease to be rock. His death in 1994 might have been rock's real death, a beautiful, tragic refusal to let the music become respectable. But rock stumbled on, zombie-like, through the new millennium, its rebellion increasingly performed rather than felt.

By 2016, rock was already on life support. The genre that once threatened civilization was being taught in university courses and analyzed in academic papers. Its greatest practitioners were being inducted into honors societies and invited to state dinners. The three-chord rebels had become elder statesmen, their dangerous lyrics now quoted by politicians and printed on inspirational coffee mugs.

Then came October 13, 2016, and the Swedish Academy decided to honor Bob Dylan with the Nobel Prize in Literature. In any other context, this would be cause for celebration. Dylan's lyrical achievement is undeniable, his influence immeasurable, his artistry profound. But in awarding him literature's highest honor, the Academy didn't just recognize a great artist; they effectively pulled the plug on rock's life support.

Because here was the man who sang "The Times They Are a-Changin'" being celebrated by the very establishment that had spent decades trying to prevent those times from changing. Here was the voice that told us not to trust anyone over thirty, now being honored by an institution older than some European monarchies. The irony would have been delicious if it weren't so heartbreaking.

Dylan himself seemed to sense the weight of the moment. His initial silence about the award felt less like arrogance than like grief. The recognition that accepting the honor meant joining the very club that rock had spent its entire existence trying to avoid. When he finally gave his Nobel lecture, it felt like a eulogy, a gentle, melancholy meditation on art and authenticity from someone who understood that the moment had changed everything.

The tragedy isn't that Dylan didn't deserve the prize; he absolutely did. The tragedy is that rock and roll couldn't survive being worthy of it. The genre that had thrived on being misunderstood, dismissed, and disapproved of couldn't exist in a world where it was celebrated by Nobel committees. Rock's power had always come from its outsider status, its ability to speak for the disenfranchised, the rebellious, the magnificently wrong. How do you rebel against an establishment when you have become the establishment?

What remains is a beautiful corpse. We still have the forms and sounds of rock, carefully preserved in streaming playlists and heritage acts. Classic rock radio plays the revolutionary anthems of yesterday like funeral dirges. New bands still form, still make loud, guitar-driven music, still pose for photos in leather jackets. But the spirit, that essential, indefinable thing that made rock dangerous, has departed for other venues.

Perhaps it's migrated to hip-hop, which still maintains rock's original DNA of truth-telling and establishment-challenging. Perhaps it lives in electronic music's boundary-pushing experimentation. Perhaps it's waiting to be reborn in some garage or bedroom studio, in the hands of teenagers who haven't yet learned that rebellion can be respectable.

Rock and roll gave us sixty-five beautiful, chaotic, transformative years. It taught us that three chords and an attitude could change the world, that authenticity was more important than technical perfection, that sometimes the most profound truth could be found in the space between a guitar chord and a scream. It showed us that music could be a weapon, a religion, a revolution disguised as entertainment.

We should mourn its passing not because it failed, but because it succeeded too well. Rock and roll died because it won. It transformed culture so completely that it became part of the establishment it had fought against. It died because we loved it so much we couldn't let it remain dangerous. We preserved it, analyzed it, honored it, and in doing so, we killed the very thing that made it alive.

Rest in peace, rock and roll. You were too beautiful for this world, too honest for polite society, and too important to remain respectable forever. Somewhere, in some parallel universe, you're still seventeen, still dangerous, still playing your three chords like they could save the world. And maybe, just maybe, they still can.

As long as there are three chords and a guitar, rock and roll will never die