In the golden age of American radio, beneath the smooth sounds of rock and roll and doo-wop, lurked a dark practice that would eventually shake the broadcasting industry to its core. The payola scandal of the 1950s exposed a system of corruption where record companies secretly paid radio disc jockeys to play specific songs, manipulating the music charts and deceiving millions of listeners.

The term "payola," a combination of "pay" and "Victrola" (an early record player), described the practice of music industry professionals providing payment or gifts to radio stations and DJs in exchange for airplay. These payments came in various forms: cash, royalty rights, or expensive gifts. While not technically illegal at the time, payola created an uneven playing field where musical success depended more on financial backing than artistic merit.

By 1959, public suspicion about radio programming practices reached a boiling point. The House Legislative Oversight Subcommittee, already investigating television quiz show scandals, turned its attention to radio. The investigation revealed a widespread system of corruption that reached the highest levels of the broadcasting industry.

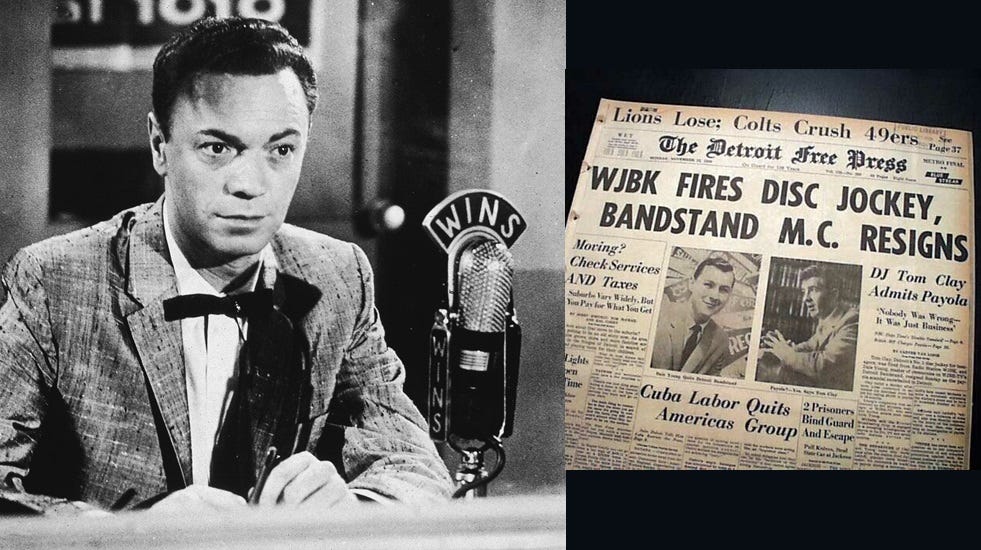

No figure embodied the payola scandal more than Alan Freed, the influential DJ credited with popularizing the term "rock and roll." Despite his genuine passion for rhythm and blues and early rock music, Freed became the scandal's most prominent casualty. Investigators discovered he had accepted payments and co-writing credits for songs he played, leading to his dismissal from WABC radio. His downfall symbolized the end of an era in broadcasting.

American Bandstand host Dick Clark, another prominent figure investigated during the scandal, managed to emerge relatively unscathed. Unlike Freed, Clark divested himself of music-industry holdings when questioned about conflicts of interest. His cooperative attitude with investigators and swift action to address concerns helped preserve his career.

The scandal led to significant reforms in the broadcasting industry. In 1960, Congress amended the Federal Communications Act to make payola illegal. The new law required broadcasters to disclose any payments received for airing specific content. Radio stations implemented strict policies against accepting gifts or payments from record companies.

The payola scandal fundamentally changed how music reached the airwaves. Record companies had to develop new, legitimate promotional strategies. Independent artists and smaller labels, previously shut out by the pay-for-play system, gained fairer access to radio airplay. However, some critics argue that more subtle forms of influence, such as commercial radio's tight relationships with major labels, continued to shape programming decisions.

The 1950s payola scandal remains a cautionary tale about the intersection of art and commerce in broadcasting. It highlighted the need for transparency in media and demonstrated how public trust can be compromised when financial interests secretly drive creative decisions. The reforms it sparked helped establish ethical standards that still influence broadcasting today, though debates about music industry influence over radio programming continue in new forms.

The scandal marked the end of radio's first golden age but ushered in an era of greater accountability in broadcasting. While payola-like practices occasionally resurface in different guises, the 1950s scandal served as a watershed moment that forever changed how America's airwaves are regulated.